Classification: Musical Instrument Recognition

Contents

Classification: Musical Instrument Recognition#

Several earlier studies have applied FSL to sound classification with the focus on non-musical audio such as environmental sounds and speech[36][37]. Methods and findings in these studies should be transferable to some degree to the classification tasks in the MIR since most of the proposed methods are not audio domain-specific. More recently, FSL is applied to musical instrument classification leveraging the hierarchical relationship between instrument classes.

Musical Instrument Recognition#

Musical Instrument Recognition is the task of labeling audio recordings of musical instruments. This task is important for many applications, particularly for organizing large collections of music samples and audio tracks within a Digital Audio Workstation (DAW).

Although musical instrument recognition is a well-researched problem in MIR, there are many challenges to overcome before musical instrument recognition systems become prominent in DAWs.

Musical instrument recognition is a particularly challenging task because most publicly available datasets only cover a very small subset of the instruments that exist across cultures in the world. For example, the Medley-solos-DB is one of the most prominent musical instrument recognition datasets in the MIR community, yet it only contains audio and annotations for eight instrument classes. Other datasets, like MedleyDB 1.0 and 2.0 contain a larger number of instrument classes (above 50) but contain very few examples for the majority of the instrument classes.

To make the problem even more challenging, musicians and end-users of musical instrument recognition systems often desire a level of granularity that is not present in existing datasets. For example, a drummer may want to differentiate between two different types of cymbals (e.g. crash cymbal vs splash cymbal).

This is a scenario suitable for few-shot learning, as the end user may have a few annotated examples of the instrument classes they would like to identify. With a bit of human effort, few-shot musical instrument recognition systems can make musical instrument recognition useful for users wanting to classify beyond the same 10-20 instrument classes that are present in most datasets.

Hierarchical Prototypical Networks for Musical Instrument Recognition#

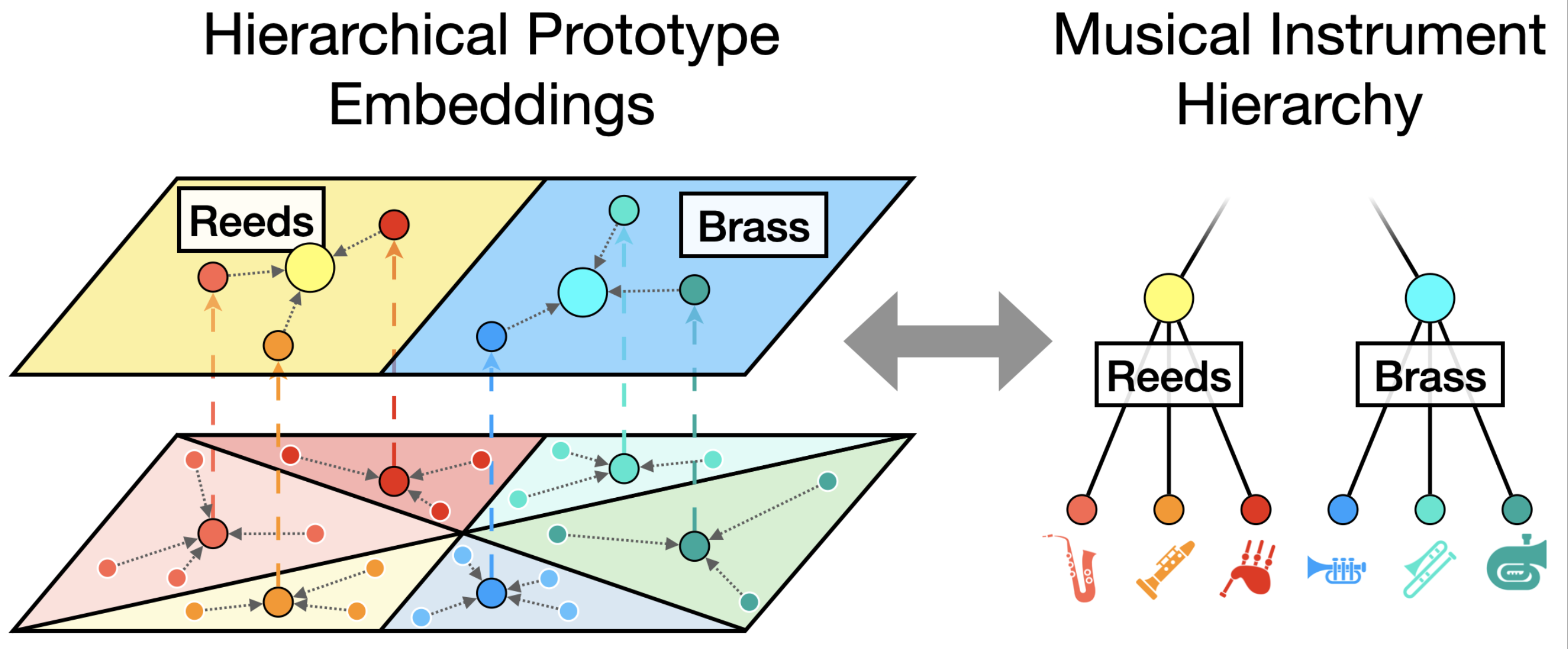

Hierarchical prototypical networks [12] are a recent approach for few-shot learning for musical instrument recognition. This approach takes advantage of the hierarchical nature of sound production mechanisms in musical instruments [38] to learn an embedding space that is better at identifying previously unseen musical instruments that share hierarchical relationships with instruments in the training set.

The Key Idea: Aggregating Prototypes Hierarchically#

Hierarchical prototypical networks [12] are very similar to standard, non-hierarchical prototypical networks [16]. Hierarchical prototypical networks are trained to mirror a label hierarchy, like a musical instrument hierarchy, by aggregating prototypes hierarchically.

To recap on our foundations chapter, a non-hierarchical prototypical network computes a prototype for each class in the support set, and then uses each prototype to compute a distance to each example in the query set. The class with the smallest distance to the query set is the predicted class. This allows the model to learn a meaningful embedding space where similar classes are close to each other, and dissimilar classes are far apart. A hierarchical prototypical network takes this process a step further, by taking the prototypes for each class in the support set, and aggregating them again into prototypes for prototypes.

Consider, for example, the classification task illustrated in the figure above. The fine-grained level of this classification task is a 3-shot, 6-way few-shot task, where we need to discriminate between recordings of saxophone, clarinet, bagpipes, trumet, trombone, and tuba.

A regular prototypical network would compute a prototype \(c_k\) for each of these classes, \(c_{sax}\), \(c_{clari}\), \(c_{bagpipes}\), \(c_{trumpet}\), \(c_{trombone}\), and \(c_{tuba}\). It would then use these prototypes to compute a distance to each example in the query set, and produce a probability distribution to compute a loss against the ground truth labels.

A hierarchical prototypical network would do this same process, but it would also aggregate the prototypes for each instrument into prototypes for instrument families. That is, it would compute a prototype for the brass family by averaging all brass instrument prototypes together: \(c_{brass} = \frac{1}{3} (c_{trumpet} + c_{trombone} + c_{tuba})\). Likewise, it would compute a prototype for the reed family by averaging all reed instrument prototypes together: \(c_{reed} = \frac{1}{3} (c_{sax} + c_{clari} + c_{bagpipes})\). Now that prototypes have been collected for this second level of the hieararchy, we can produce a second probability distribution for each query example between two instrument families (reeds and brass) to compute a loss against the instrument families of the ground truth labels.

This process can be repeated over and over, for each level in a hierarchy. For example, reeds and brass could be aggregated together to form woodwinds prototype, and so on.

This leads us to having a separate classification task for each level in the hierarchy. In the example above, this leaves us with a 3-shot, 6-way task for the instrument level, and a 3-shot, 2-way task for the instrument family level. The cross-entropy loss for each of these tasks can be aggregated together to produce a single loss for training our few-shot model.